Booker T. or W.E.B.?

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois quarreled over how best to educate Black American youth. While both were looking for the best way to improve African Americans’ overall place in the U. S. economy, Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute, argued that young Black people should train themselves “in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service.” Du Bois, a young Harvard graduate on his way to becoming one of the intellectual giants of the twentieth century, argued for the “education of youth according to ability” in publicly supported colleges and universities. Fortunately for the United States, Du Bois won that argument. Had African Americans been confined to vocational and technical training and not had access to publicly supported university education, there would have been no Brown vs. Board of Education, the Civil Rights movement would have been dramatically different, Martin Luther King, Jr. would not have been the leader he was, and Barack Obama would not be president.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois quarreled over how best to educate Black American youth. While both were looking for the best way to improve African Americans’ overall place in the U. S. economy, Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute, argued that young Black people should train themselves “in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service.” Du Bois, a young Harvard graduate on his way to becoming one of the intellectual giants of the twentieth century, argued for the “education of youth according to ability” in publicly supported colleges and universities. Fortunately for the United States, Du Bois won that argument. Had African Americans been confined to vocational and technical training and not had access to publicly supported university education, there would have been no Brown vs. Board of Education, the Civil Rights movement would have been dramatically different, Martin Luther King, Jr. would not have been the leader he was, and Barack Obama would not be president.

The state of Washington now finds itself at a crossroads similar to that faced by Washington and Du Bois.

The recent state budget cuts told a story about higher ed and established a pecking order that was readily apparent at the Higher Education Coordinating Board meeting last May 12. At that meeting, after the chairs of the House and Senate Higher Ed committees tried to reassure the Board that the cuts to higher ed were not that bad, University of Washington president Mark Emmert replied with frustration, “You can say whatever you want, in the end you’ve cut my university’s budget by twenty eight percent.” He went on to point out that, with the 2009-11 state budget, Washington’s public universities will have “crossed the Rubicon” to a land where state appropriations will be less than half of their budgets. While Emmert spoke with eloquent exasperation, Charlie Earl, the executive director of the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges, remained relatively quiet and almost purred when he did speak, knowing that the cut to community college budgets had been about a quarter that to the universities. When someone else on the Board observed that the legislature had, with its budget, marked 2-year higher education as a “public good” and 4-year higher education as a “private good,” no one disagreed.

The recent state budget cuts told a story about higher ed and established a pecking order that was readily apparent at the Higher Education Coordinating Board meeting last May 12. At that meeting, after the chairs of the House and Senate Higher Ed committees tried to reassure the Board that the cuts to higher ed were not that bad, University of Washington president Mark Emmert replied with frustration, “You can say whatever you want, in the end you’ve cut my university’s budget by twenty eight percent.” He went on to point out that, with the 2009-11 state budget, Washington’s public universities will have “crossed the Rubicon” to a land where state appropriations will be less than half of their budgets. While Emmert spoke with eloquent exasperation, Charlie Earl, the executive director of the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges, remained relatively quiet and almost purred when he did speak, knowing that the cut to community college budgets had been about a quarter that to the universities. When someone else on the Board observed that the legislature had, with its budget, marked 2-year higher education as a “public good” and 4-year higher education as a “private good,” no one disagreed.

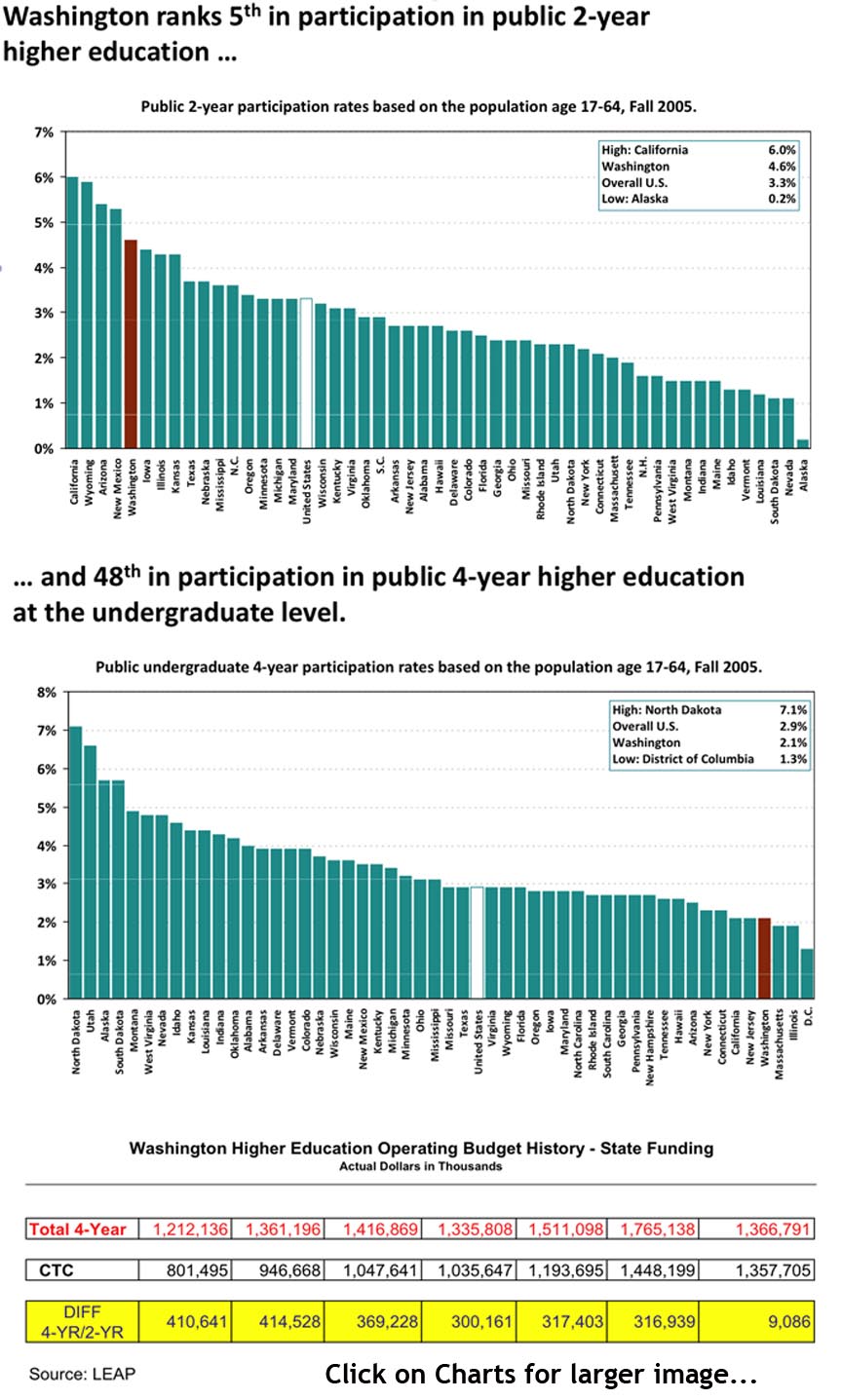

This is, of course, not news to anyone who has been paying attention to higher ed in Washington. We may only now have reached the other side of the Rubicon, but we’ve been wading across it for a long time. Paradoxically, a state that depends on businesses and industries that depend on a university-educated work force has been steadily disinvesting in its universities. Washington, by virtue of its high-tech and information-based industries, has one of the highest percentages of bachelor’s degrees per capita, but most of those degrees are imported from other states. We live in a state of great natural beauty and no one has to have an arm twisted to move here. Washington can afford to make a university education a private commodity because it has the luxury of outsourcing the education of its highest paid workers to other states. Thus, a state teeming with baccalaureate and graduate degrees has one of the lowest ratios of citizens who participate in 4-year higher education. At the same time, state participation rates in 2-year colleges have long been among the highest in the nation. This huge disparity between 4-year and 2-year participation rates is not an accident, but the result of years of legislative funding decisions.

A kind of dubious populism has animated a lot of the state’s commitment to community and technical colleges and certainly played a large role in justifying the very different ways that 2-year and 4-year colleges were treated in the latest budget-cutting carnival. The argument is that community and technical colleges provide the immediate vocational and technical training that puts people back to work and stimulates the economy, while universities trade in the more nebulous and less employable liberal arts and sciences. So for many people, the idea that increasingly, the state defines a university education as a private luxury makes sense. If you want to get a good job as a nurse or computer technician, the state will support that—if you want to dabble in poetry and history, you’re on your own. And this notion of community colleges as salt-of-the-earth, real-world training grounds and universities as snotty sanctuaries for dilettantes is not just a perception limited to the people who write comments on blogs. In the wake of the devastating budget cuts, politicians from all points on the ideological compass felt perfectly comfortable telling university students, faculty, and staff that we were just too elitist.

This attitude is not only wrong, it is itself elitist.

The truth is that the difference between a community college and a university is not the difference between getting a job and disappearing into your own navel. It is the difference between the job you get with an Associate’s degree and the job you get with a Bachelor’s degree. The nicest offices at Boeing, Microsoft, Washington Mutual, and REI all have four-year college degrees hanging on their walls. On average, a person with a Bachelor’s degree (even people with those worthless humanities degrees) can expect to earn over a million dollars more in a lifetime than a person with an Associate’s degree. The students with those English, History, and Philosophy degrees go on to law school, business school, and highly paid entry-level jobs. Most of our state legislators have bachelor’s degrees and many have advanced degrees. An associate degree qualifies you to take your place in the economy, a bachelor’s degree moves you up to the places where the economy gets planned and managed.

The big losers in the state’s abandonment of its universities are Washington’s citizens, especially those at whom the populist rhetoric is aimed. Everyone—the Higher Education Coordinating Board, the legislature, the Office of Financial Management, the education community—agrees that Washington demographics are such that, if the state is to be competitive, the next several generations of college students must come from families that live below the middle class and have little or no tradition of higher education. The state’s growing Latino population has been repeatedly singled out as one that must be better represented in higher ed. The HEC Board Master Plan and the cacophony of higher ed bills that appear in every legislative session make it seem that the state is intent on making higher education attainable and available to people for whom it traditionally hasn’t been. But when we get past all the talk and actually hear the story that the budget tells, it becomes clear that the state has told us that it only wants the well off and those with degrees from other states striving to contribute to the upper levels of Washington’s economy. The state has become a minority investor in state universities and turned them into a private good only for those with the private resources to afford them. The more the state privatizes its universities, the more they will have to act like private universities, depending on grants, private fundraising, and increasingly steep tuition. No matter how valiantly financial aid tries to keep up, this will inevitably make our state universities more and more the playground of the privileged.

Everyone else is being told to set their sights no higher than the vocational goals of Booker T. Washington.