Skin in the Game

By 2004, just two years after it had become legal for university faculty in Washington to unionize, four of the six universities in the state had faculty unions. In part, this was about salaries—Washington’s tradition of paying below market salaries for a world-class university system has caught up with us. But the main reason faculty went out and got a union is because we’d lost our voice.

Washington State has 6 university boards of trustees, 34 community college boards of trustees, a 9 member State Board of Community and Technical Colleges with 140 staff, and a 10 member Higher Education Coordinating Board with 94 staff. These people make recommendations to the legislature about higher education, set the policies that govern our institutions, and control the budgets of our colleges and universities. These dedicated and well-meaning people exert tremendous influence on how teachers teach and how our students learn, but their contact with teachers and students rarely takes the form of anything more than brief testimony. They have virtually no contact with actual classrooms or the daily learning exchange between professors and students.

Washington State has 6 university boards of trustees, 34 community college boards of trustees, a 9 member State Board of Community and Technical Colleges with 140 staff, and a 10 member Higher Education Coordinating Board with 94 staff. These people make recommendations to the legislature about higher education, set the policies that govern our institutions, and control the budgets of our colleges and universities. These dedicated and well-meaning people exert tremendous influence on how teachers teach and how our students learn, but their contact with teachers and students rarely takes the form of anything more than brief testimony. They have virtually no contact with actual classrooms or the daily learning exchange between professors and students.

These boards have hundreds of people working for them and there is not one regular faculty member among them. None, zero, zip, zilch.

Again, there can be no doubt that the people who populate these boards and their staffs have the best of intentions and genuine dedication to higher education in Washington. But they do not have the perspective of the professors who deliver that education every day. They bring the valuable, but still removed, points of view of statisticians, policy analysts, politicians, lawyers, administrators, and business leaders. The governors and legislators who appoint and fund our boards and their staffs spend most of their time trying to juggle a budget that has more and more demands and less and less revenue. Higher education has traditionally been the back on which Washington’s books are balanced, so our boards and their staffs are routinely charged with finding ways to produce Washington’s high quality higher education for less. All of their task forces and subcommittees, officially charged with assessment or accountability, tuition study or mission statement, transfer policies or technology possibilities, are all ultimately about trying to squeeze more blood from the stone.

In this context, it’s easy enough to see how the faculty, with so much skin in the game, could come to have so little voice. Our first concern is always providing the best possible education for our students. Inevitably our interests, perspectives, and priorities diverge from those of the people who govern our workplace. We don’t feel the relentless external pressure that they do and they don’t see the effects those pressures have on our students. They think and talk in terms of outputs and cost structures and greater efficiencies, so it is completely understandable, even inevitable, that they would come to see faculty mostly in terms of labor costs.

So now we have a union and our union has a web site and our web site has this blog, which is one of the ways that we will now be taking our voice to the streets, both virtual and real, in the hope that it will also be heard in the capitol. Over the last three years, we have established ourselves on our campuses as advocates for faculty and students and developed good relationships with our administrations. Last year we watched as our institutions got their butts kicked as the state legislature used Washington’s university system as its rainy day fund before they used the actual rainy day fund.

In the midst of that bloodletting, we were called elitist, arrogant, wasteful, unaccountable, and out of touch. Legislators, including some of those on the higher education committees who should know better, openly derided our universities on television and in the newspaper. New task forces and subcommittees were created, funded and sent out to find new ways to cut us even further.

The public discussion of our universities, when it takes place at all, is filled with inaccuracies and distortions. Polls show that while people generally have favorable impressions of our universities, they are under the deeply mistaken impression that we are well funded. Pundits and policy makers regularly float the fantasies that things like on-line learning, three-year degrees, and baccalaureate degrees from community colleges will solve all our problems. Much of the received wisdom about universities is conceived and circulated without any reference to the realities of universities.

These are the things we know:

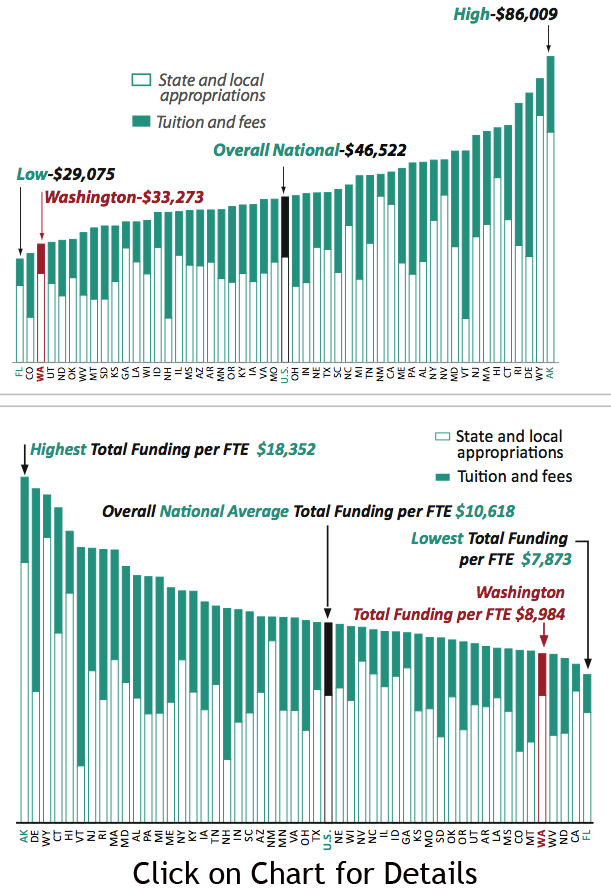

–Washington has the most productive and cost efficient university system in the country.

–Washington’s universities are consistently rated among the best in their categories.

–Washington’s universities are underfunded to the point where the state has been forced to become a national leader in the importation of baccalaureate degrees.

–Washington’s children are in danger of having little or no access to the 4-year degrees they will need to be the leaders in Washington’s economy.

These are the things we know, but they are not necessarily the things that the citizens of Washington and their representatives know. In the coming months we will be using this blog to give a faculty perspective on state politics and make the case for our public universities. Along the way, we hope to help make the coming destruction of Washington’s public universities more of an issue than it has traditionally been for voters.

In a better world, our universities would be fully funded and our union would need only work to ensure faculty working conditions and thus student learning conditions were the best they could be.

In this world, our union is determined to help save Washington’s universities.