The Curse of the Ruling Classes

Let’s start with an observation that should by now be axiomatic: All bosses are overpaid. And most of them are insulated from and clueless about the way their attitude and privilege come off to the rest of the world. If we could all just agree to this truth that is even older than rapacious capitalism, we could get past the reddest herring in the debate about higher education in Washington State.

In a recent editorial in the Seattle Times, Nicole Brodeur lent her indignant voice to the chorus of moaning about UW President Mark Emmert’s millions and Provost Phyllis Wise’s new gig moonlighting for Nike. After President Emmert dropped by the Times to talk about the latest round of cuts to Washington’s universities, Ms. Brodeur was compelled to write:

“I sat there and listened to Emmert lament the cuts that would come, the students who would suffer. The diversity that would die. The futures dashed.

“But all I could think about was Emmert’s $905,000 annual compensation; the second highest among public university presidents nationally.”

That’s a bit like listening to the weatherman tell you about the hurricane that’s coming and refusing to evacuate because he’s wearing a nice suit.

The message isn’t wrong just because the messenger is arrogant or tone deaf. Whatever else Mark Emmert may or may not be, he’s dead right about the impact of draconian cuts to university budgets on opportunity and economic vitality in this state. Unless something dramatic happens to turn things around, Washington’s universities will become increasingly smaller and more private and Washington’s citizens will be put at more and more of a disadvantage in the competition for Washington’s best jobs.

Brodeur and all the others who want to scapegoat the UW president always make the childish connection between Emmert’s swag and the rising costs of going to college, suggesting that if top administrators were just paid less then university budget problems would go away and everyone could afford to go to college.

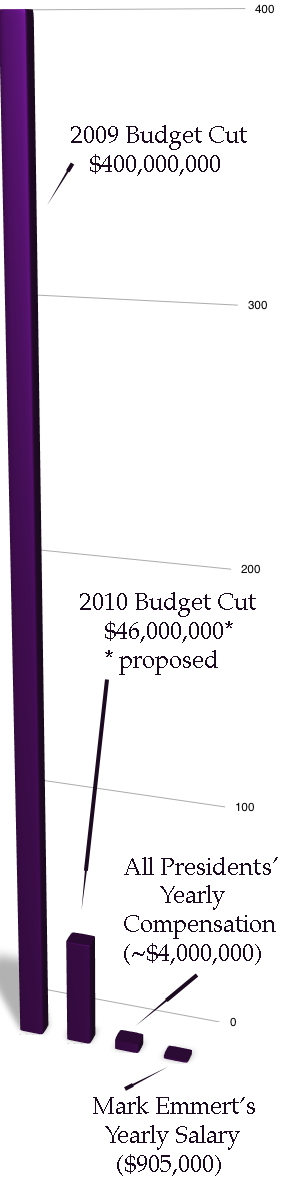

Well, do the math: There are six university presidents in this state. None of the rest of them make Emmert’s money, but they’re all living very well and they all get houses and country club memberships. If you sacked all of them tomorrow you would save the state about $3 million dollars. (You would, of course, be left with a bunch of universities without presidents, but let’s not quibble.) Throw in the housing allowances and the cars and the golf and maybe you’re up to $4 million.

Last year the legislature cut state support to Washington’s universities by $400 million. The governor’s recently released budget is proposing to cut them by another $46 million this year. Presidential salaries are just a drop in an oil drum. If Emmert had responded to the many calls to give back some of his salary, it would have been a purely symbolic gesture. (And as long as we’re looking for pointless conversations, we could debate which presidential gesture was more hubristic, Emmert’s coy assertion that “everything” was on the table when he had no intention of cutting his salary, or Washington State University President Elson Floyd’s pious give-back of a hundred grand at the same time that he was making sure that WSU students will no longer be able to study Theatre or German.)

The cost of public universities has not gone up because of outlandish executive salaries, and it has not gone up because of the salaries of university faculty and staff, which have struggled to keep pace with inflation. It has gone up almost solely because the state has been relentlessly redefining public university education as a private good. State support for state universities has been steadily declining over the past 15 years and precipitously declining in the last two years.

Ironically, it is exactly this declining state support that has led to the need for CEO-type presidents. In the early to mid-twentieth century, when public universities were still for the public and still about education and research, the college president was still an academic who didn’t get that much more than everyone else on the faculty. He (and in those days it was always he) had to clean up O.K. and know which fork to use, but mostly the job was running the university. As universities have become more and more entwined with corporations and less and less supported by the state, the job of president shifted more and more toward the external. As universities are forced to become more and more like businesses, regents and trustees are forced to go looking for corporate rainmakers to run them. The best way to keep executive compensation under control would be to restore the public funding that would allow public universities to operate more like universities and less like corporations.

Public universities in Washington are on the brink of not being public any more. The universities were cut disproportionately last year and the governor’s proposed higher education cuts for this year again slice deeper into the universities than the community colleges. The decisions made in this legislative session about taxes, funding, tuition, and financial aid will have a profound impact on students for generations to come. We have serious problems and we need serious people trying to solve them. What we don’t need is a lot of distracting bluster about Mark Emmert’s tax bracket. Let’s hope that our legislative and media friends don’t waste a lot of time grandstanding about the banal fact that all bosses are overpaid.