The Price of the Ticket

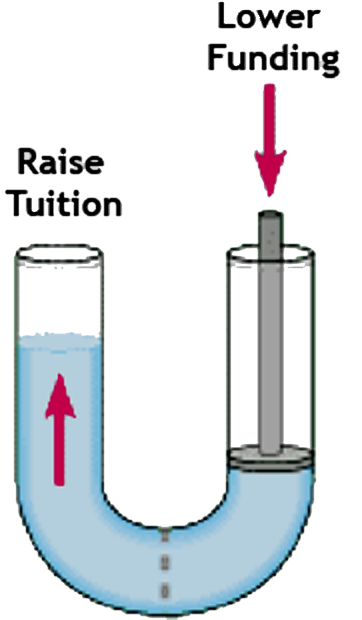

The function of tuition at state universities is straightforward. As state appropriations decline, the burden of the cost of education is shifted to students and tuition goes up. As tuition goes up, people with less money have a harder time going to college, which is antithetical to the mission of a public university.

Despite this simplicity, Washington’s Higher Education Coordinating Board has done fifteen tuition studies since 1990, and right now they are finishing a sixteenth. That’s almost a study a year. Between the consultants, the staff time, and the hearings, the money the state has spent studying tuition could have paid the tuition of dozens of students.

Despite this simplicity, Washington’s Higher Education Coordinating Board has done fifteen tuition studies since 1990, and right now they are finishing a sixteenth. That’s almost a study a year. Between the consultants, the staff time, and the hearings, the money the state has spent studying tuition could have paid the tuition of dozens of students.

That the state has been almost continuously engaged in the study of the relatively simple issue of tuition is probably a result of the fact that tuition is politically very sensitive. Tuition studies are more about political cover for raising tuition than they are about discovering anything new. That is certainly the case with the latest study.

In 2007, still basking in the glow of Washington Learns and aspiring to enter the pantheon of Global Challenge States, the state legislature passed a law limiting tuition increases at Washington’s institutions of higher education to no more than 7% per year. This got the Democratic caucus some short-term love from students (a pretty unreliable voting block when Barack Obama is not on the ballot), but from a strictly political point of view, this was probably a dumb move. Because when the bottom fell out in 2009 and the state used 4-year universities as its rainy day fund, the legislature had to renege on its promise and allow universities to raise their tuition by 14% in order to keep from crumbling under 25-30% cuts to state appropriations. Republicans running in 2010 will certainly chastise Democrats for making a law in one session and then immediately breaking it in the next. And of course they will season that charge with lots of pious talk about students and how our children are our most valuable resource.

That’s what made raising the tuition ceiling in 2009 such a “tough vote” for legislators. The night they did it was one of the most emotional of a pretty emotional session. And many legislators haven’t forgotten it, feeling that the universities haven’t shown enough gratitude for the courageous choice they made to let us bill our students for the draconian cuts they made to our budgets.

So of course, as part of the political cover for forcing the universities to balance their budgets on the backs of their students, the legislature ordered the HEC Board to do yet another tuition study. The draft of this latest study is now available on the HEC Board website. It is yet another earnest and well-documented attempt to outflank stubborn facts and try to imagine a world in which state appropriations to universities can continue to decline and college can remain affordable.

The fundamental contradiction in the study is that it insists that the state return to funding at least 55% of university education while assuming that nothing will change about state appropriations or the state’s goofy and wildly regressive boom-and-bust revenue system. This is a tribute to the HEC Board staff’s ability to imagine other worlds, but in this world, the only way that could happen is if the universities dramatically reduced tuition, which would, of course turn the campuses into ghost towns.

At last Thursday’s HEC Board meeting, representatives of the universities lined up to express their concerns with the study and its possible consequences once it reaches the legislature. In many ways, the discussion was a preview of what could happen in the legislative session. On one side, we had the universities, whose state appropriations have been cut beyond recognition. They have no faith that the state will support public universities and thus want to control their own tuition in order to keep excellent universities from crashing into mediocrity. On the other side, members of the HEC Board feel that their duty is to make sure that continuously rising tuition does not put a university education out of reach for middle class families. Both sides are right. And as long as we continue to talk about tuition isolated from everything else that affects it (as the latest tuition study often does), the two positions will remain irreconcilable.

Listening to the discussion on Thursday, it was easy to get the feeling that this was the warm-up, the undercard for the main event in Olympia, where the number one contender, UW President Mark Emmert, will square off with the undisputed champion, HEC Board Executive Director Ann Daley for fifteen rounds over whether or not the universities will be granted tuition-setting authority. The corridors of the capitol will surely be livelier for that struggle, but it will not serve the students, the universities, or the state. If the HEC Board and the universities go to Olympia fighting over the nuances of who gets to set tuition, then legislators will do what they do best. They will turn away from the in-fighting higher education people and toward groups who have learned the value of speaking with one voice.

When the Thursday conversation started to put tuition into a larger context, most of the differences and tensions between the HEC Board and the universities disappeared. Everyone agreed that there should be more state support for our universities. As soon as you acknowledge the hydraulic relationship between tuition and state appropriations, it’s easy enough to get everyone to admit that the best way to keep tuition low is to increase state appropriations.

And that’s what the tuition study that goes to the legislature should lead with. The argument is simple and it goes something like this:

1. Washington’s universities are about the best bang for the buck in the country, producing high quality degrees at well below average costs.

2. Tuition and state support are hydraulically related—as state support goes down, tuition goes up.

3. As tuition goes up, people with less money have a harder time going to college, which is antithetical to the mission of a public university.

4. Thus, the best and only way to keep universities affordable for Washington’s citizens is to dramatically increase state support. Everything else is just nibbling around the edges.

Policy purists will argue that this goes beyond the bounds of a tuition study and runs the risk of politicizing the work of the HEC Board. We here at the blog would respectfully suggest that tuition was politicized a long time ago and that the HEC Board should not be in the business of producing reports that can be used as faux populist manifestos for further decimating our universities.

The argument for more state appropriations should be page one of the Tuition Study (and the System Design Study and the various Technology studies . . .) and everything else currently in the report should be relegated to footnotes. That way, everybody—the HEC Board, the students, the faculty unions, the university administrations—could all enter the upcoming legislative session with a united front.

In these times, anything less than that is suicidal.